Updated 8/8/24. I live in a headspace that assumes everyone is up to date on the nuances of things and that I don’t need to write about it because it’s old news. And then I read this article in the Pink Sheet on how Medicare-negotiated prices may not get favorable coverage and realized that nope, people don’t know. And while the article is really good, I thought a breakdown with some visuals might make it come alive for those who don’t live in this every day.

Background: The Inflation Reduction Act has Medicare setting the price of ten drugs starting in 2026. These drugs were chosen because they had the highest total spend in the Medicare prescription drug benefit (Part D).

For the first year, most of the drugs chosen likely have high rebates. They have been on the market for a long time and are in competitive classes that would require them to give back significant rebates to payers to have formulary access. But Medicare is going to “negotiate” prices based on either a Maximum Fair Price calculation (% of price of drug going to non-government entities with the % going up depending on how long since launch) OR a weighted average of the Part D rebated price or some other magical calculation which we don’t know yet*

But let’s do the math …

Note – I’ve kept this simple. It’s an example.

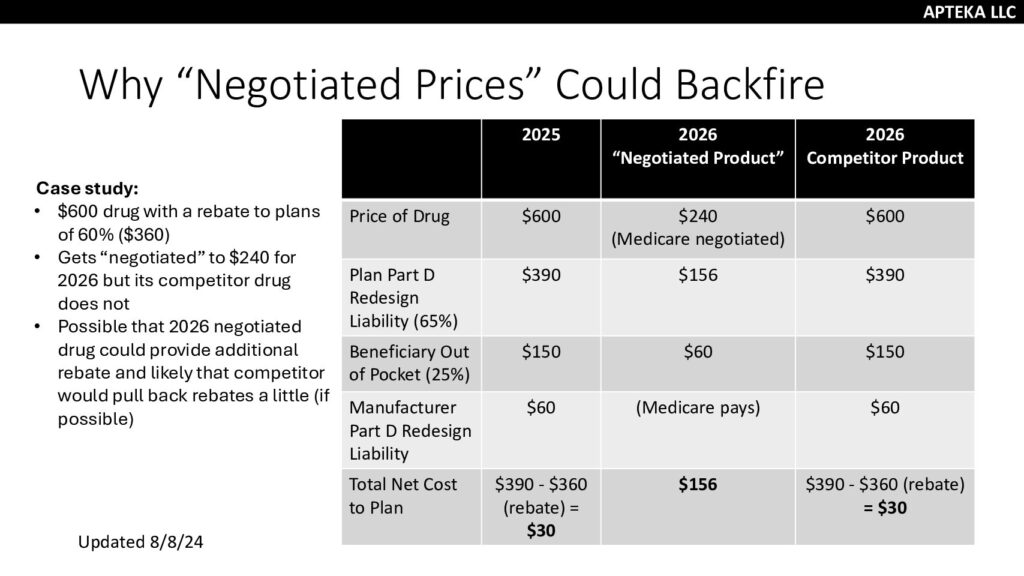

Example here is a $600 drug that is being “negotiated” starting in 2026. But in 2025, the manufacturer would owe $60 (10% of the $600) in Part D liability (unless the person was in catastrophic, but let’s keep it basic). The plan would owe $390 (65%) and the patient would owe $150. That’s a total of $600.

The manufacturer would also provide a rebate to the plan for 60% for formulary coverage. That means the manufacturer has made about $180 out of the $600 (price minus liability of $60 and rebate of $360) and the plan has paid $30 out of the $600 ($600 – $150 from patients – $420 from manufacturers.)

In 2026, the Medicare price for the drug is reduced to $240. A win! The beneficiary is now responsible for $60 (25% of the $240) and the plan is responsible for $156 (65% of $240). Manufacturers who are “negotiated” do not owe the 10%/20% liability for the drugs in the program, the government pays that liability. The liability to the plan overall is $156. The manufacturer has provided $360 worth of value in the negotiated price.

A competitor that is not negotiated, would face a similar story to the 2025 drug but now looks better than the negotiated competitor because it is a lower price AND providing cash to the plan as part of the rebate. And floating cash is better than not having cash. PLUS, plans get to keep a % of the amount over the plan bid which means those rebates become profit. (If you want to learn more MedPAC payment basics or Milliman.) My understanding of the math is that plans will keep less of each rebate dollar in 2026 compared to 2024 BUT it is still more valuable than a lower price. So we’re stuck in a high price, high rebate cycle.

It is possible that the “negotiated” drug will come up with another additional revenue to make it more equitable to the plan but they can only go so low. It does partially depend on what plans are required to do by CMS.

But you can see that negotiated prices aren’t awesome for plans…I’d assume parity for negotiated drugs with competitors but we’ll see how/what that means in practice.

*Am I grouchy about this? Yes. Yes I am. If you’re going to reject offers and counteroffers, those you are dealing with should be able to figure out what the rejection is based on. Rabbits out of hats are for magic shows, not government pricing.